There has been a significant increase in the number of laws aimed at preventing disinformation proposed or implemented in different countries since 2015. The increase in the use of social media platforms for news and information, the platforms’ algorithms spreading false information, anonymity overtaking accountability, and internet-specific propaganda methods such as bots and trolls illustrate the need for a different approach to the problem of false information. We have increasingly come to consume the uncontrollable flow of information onsocial media in a way that is detrimental to our lives and democracy. Hate speech and lynch campaigns show that it is becoming ever more difficult to protect ourselves in the digital space. These developments make one feel that there is a need for regulation. But unfortunately, every effort at legislating against disinformation introduces new issues and often hinders freedom of expression.

Attempts are made to prevent the spread of false information by means of imprisonment. This is an observable trend not just in Turkey but also in countries such as Russia, China, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Tanzania, Taiwan, Thailand, Kenya, Myanmar, Singapore and Malaysia. We can see that freedom of expression is seriously restricted in countries where prison sentences are imposed on those who spread “fake news”. According to the 2021 data of the Committee to Protect Journalists, 47 journalists worldwide have been arrested for spreading “fake news.” Another common feature of the abovementioned countries is that they lag behind in the areas of freedom of the press and media literacy.

Unfortunately, the steps taken in the fight against disinformation were no different in Turkey. The disinformation law – dubbed “censorship law” by the public – was passed by the Turkish parliament in October 2022. The opposition party CHP demanded the cancellation and suspension of the enforcement of this law’s 29th article, which stipulates that those who spread false information should be punished with three years of imprisonment. The Constitutional Court stated that it will examine the constitutionality of the law in the coming days.

Teyit, one of Turkey’s leading fact-checking platforms, has repeatedly shared its views on this law which the government has long desired to enact. However, unfortunately, the media, professional organizations and civil society organizations in Turkey failed to display the necessary attitude and stance until the law came to parliament.

Apart from penalizing disinformation, this law, which includes regulation of the social media, was drafted without consulting civil society nor media stakeholders. Teyit has been a leader in the field of combatting disinformation for six years, but was not approached or consulted for its expertise.

When explaining the disinformation law to the public, Turkish officials frequently referenced the NetzDG law passed in Germany in 2018. However, the NetzDG law is not directly related to fake news. It was developed over a two-year period, during which input was sought from various non-governmental organizations, associations, experts, and journalists. Efforts were made to ensure inclusivity during its development.Unfortunately, the methods used in the drafting process of the laws cited as good examples by the Turkish officials were not employed at all.

Efforts to combat disinformation should not stray from the civic space

It is necessary to take seriously the issue of the state weaking the civic actors in this field by increasing the instruments at its disposal. The disinformation law is just one of these efforts.

Other recent steps are as disturbing as the three-year prison sentence for spreading false information. The Presidential Directorate of Communications established the Center for Combating Disinformation in September 2022. Since the beginning of October, they have been publishing a weekly bulletin sharing the false information they have identified. But it is already a matter of debate which “falsehoods” and “truths” have been selected. The manipulation of truth and falsehood for the benefit of both those in power and those in opposition raises doubts about the importance of truth. Neglecting the potential harm of disinformation and treating it solely as a political tool can severely damage our trust in information.

Another step came directly from the media. The state-controlled Anadolu Agency (AA) has a separate publication called “Teyit Hattı” (“Verification Line”), which shares the truth about misinformation in social media and the press. We at Teyit believe that the greatest achievement we have made in the past six years is combining the concept of “verification” (teyit in Turkish) with the pursuit of accurate information and the habit of critical thinking. It is no coincidence that AA chose that name for its publication, just like us. However, doubts remain about the impartiality and function of AA’s verification mechanism.

As the elections draw near, it is crucial to view the actions of the government in a comprehensive manner and to emphasize the efforts of those, like us, who are working to counteract disinformation.

The danger of escaping to closed networks

The inability for individuals to freely express their political views and the lack of safety to do so is a concern when it comes to engagement and participation. The growth of state intervention and the disinformation lawmay force citizens who feel their freedom of speech is being curtailed to move their discussions to spaces where they feel more secure.

Closed communication channels such as those provided by WhatsApp, Telegram, and Facebook groups are likely to be the beneficiaries.

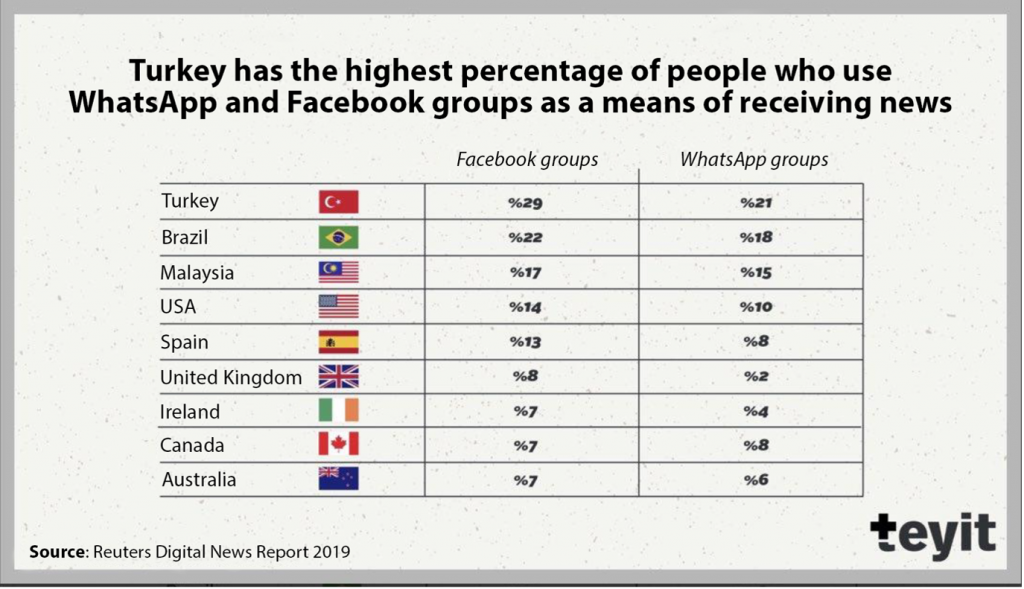

According to Reuters’ 2019 Digital Media Report, Turkey is the country where closed Facebook and WhatsApp groups are most used to access news and engage in political discussions. When access to information is hindered, we tend to trust information from people close to us, thereby strengthening our own beliefs and making us susceptible to false information.

While 40% of users in Turkey say that they trust the news they see on social media, this rate rises to 50% among those who use Facebook and WhatsApp groups. There is a significant difference between Turkey and other countries. When false information is distributed on closed platforms, fact-checking organizations are unable to easily access it and have no way of determining its extent. Trying to stop the dissemination of false information through imprisonment is likely to only exacerbate the issue and lead to an environment where we are further isolated in our own bubbles, unable to hear or listen to others.

Just because we may see less false information on the internet in the future, it does not mean that false information is not still being circulated. As Teyit, we stress the importance of prioritizing critical digital literacy –which can help us recognize false information – over actions taken by laws and the government, as these actions will not only fail to solve the problem but will make it worse.

Critical digital literacy as the solution

Governments and states that choose education over laws as a defense against false information are attempting to foster critical thinking skills in media literacy. It comes as no surprise, but Finland takes the top spot on this subject. Finnish authorities aim to address the issue of disinformation in the education system starting in primary school. Students who are taught about image manipulation and the ease of manipulating statistics will be better equipped to recognize similar fake content when they encounter it online. We, too, need to move beyond simplistic labels such as “lies” and “propaganda” when discussing false information and reveal the ways it infiltrates our lives.

Teyit has been making a long-term effort to promote critical digital literacy values. For the past three years, we have emphasized the significance of critical thinking by sharing our work and fact-checking methods with a total of 18,582 individuals at 145 events that we either participated in or organized ourselves. In 2021, we collaborated on various projects with teachers, parents, and students. We have incorporated fact-checking and critical thinking practices into classroom instruction. The Teachers Network (Öğretmen Ağı) and Teyit collaborated with 39 “Ambassador for Change” teachers from 19 different provinces to equip students with the skills needed to comprehend the issue of information disorder. We were able to observe the results of these efforts after a short period of time. Both primary and high school students started to apply fact-checking techniques in their daily lives. As for the teachers, they continued to disseminate the skills and techniques they had learned to other schools.

We are currently undertaking a project aimed at equipping university students in three major cities in Turkey with critical thinking and fact-checking abilities to safeguard democracy before the upcoming elections. In addition, our #teyitpedia hashtag category equips journalists and the general public with the tools to prevent the dissemination of false information.

Knowing that laws will not solve the problem of information disorder, we should persist in utilizing the critical thinking techniques that we have attempted and succeeded in implementing. It is crucial that the actions and efforts of states and governments in this field should be approached with the same perspective.