Freedom of press is one of the main requirements of a democratic society. As the public watchdog, the press greatly contributes to public debate and ensures accountability by imparting information about the actions and statements of those in power.

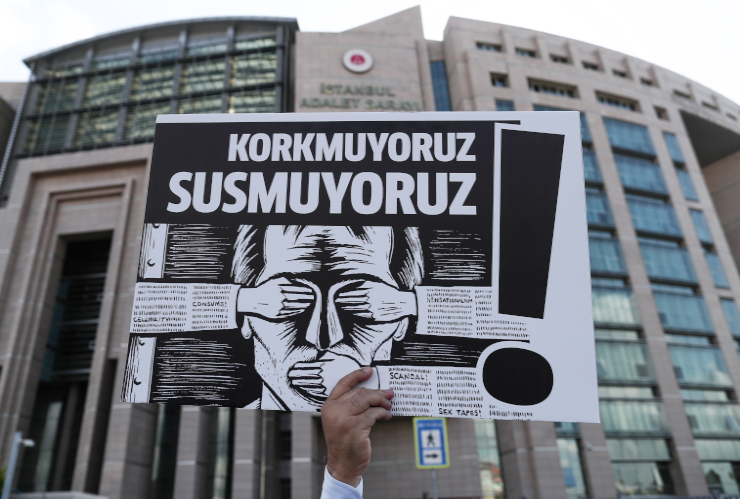

Yet despite this crucial role, there is a rising trend of heavy interference in the freedom of press by both the state and private actors around the world. Turkey is a leading example of the trend of democratic countries where press freedom faces such attacks and interference. This interference takes numerous forms and methods, including criminal investigations and prosecutions, compensation claims, broadcast and advertising bans, seizure of publications, orders to disclose sources, and the revocation of licenses or press cards. Although in many cases it is obvious that such interferences are clearly unfounded and used for repressive purposes, they often hide behind a legal façade that masks the true intentions of the intrusion. This mask is mostly composed of sloppy indictments with no concrete basis or reasoning, and arbitrary and abusive prosecution in courts. But despite the effort, the mask usually cannot hide the true repressive intentions from the public eye.

Insult charges as common practice to suppress free media

In Turkey, abusing the judicial system as a political means to suppress press freedom has dramatically increased in the last few years. In addition to anti-terror laws, insult laws are a common instrument to retaliate against journalists and others for criticism.

The Turkish Criminal Code (TCC) regulates the offense of “insult” under Article 125, which foresees a punishment of a monetary fine or up to two years in prison. The crime of “insulting the president” is separated out under Article 299 and carries a higher sentence of up to four years in prison. The use of insult laws in Turkey is widespread, and on the rise. According to the statistics published by the Ministry of Justice. between 2013 and 2019 more than 200.000 new cases were opened under Article 125 each year. The rise in cases under Article 299 is particularly worrying. While there were zero new cases in 2013 on this specific charge (p.59), this number has skyrocketed throughout the years, reaching 11,371 new cases in 2019 (p.60). Press freedom monitoring shows that criminal charges for insulting the president are filed in response to journalists’ articles, columns and opinions on social media quite frequently.

On the other hand, employing judicial means to suppress freedom of expression and the press is neither new nor particular to Turkey. There is a growing worldwide concern over such practices. For instance, “Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation”, also known as SLAPPs, have becoming more common, in which the wealthy and powerful try to prevent criticism by using existing legal rules and judicial system via insult and defamation claims. Rather than winning the case, the aim of SLAPPs is to intimidate the defendants and to deter others critics through the threat of exhausting resources and time. Considering the crucial contributions of media professionals and organizations to public debate, practices such as SLAPPS pose a serious threat to press freedom. In Turkey, insult charges filed under Art. 299 or other insult charges filed by wealthy business owners, local politicians and other public figures under Art. 125 could be easily classified as SLAPPS, since many lack sufficient basis and evidence.

In particular, the lengthy trial procedures in Turkey – comprising of the first instance court, regional appeal court, Supreme Court of Appeals, and, if applicable, the Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), as well as possible retrials – could lead to media professionals’ being exposed to duress, both materially and psychologically. The acquittal alone would not remedy the damages, pecuniary or non-pecuniary, that the party experienced or the time that has been lost.

However, as per the Turkish Constitution and binding international norms such as the European Convention on Human Rights, Turkey is obligated to create a favourable environment for freedom of expression and press to be exercised effectively and to not subject right holders to unjustified interference. Therefore, the state must eliminate and remedy all practices that run counter to freedom of expression and press. Notably, international recommendations call for the repeal of all criminal insult and defamation laws due to the ease with which they can be abused. However, IPI research suggests that these obligations are not being fulfilled in Turkey. On the contrary, judicial measures seem to be applied against critical voices disproportionately.

Lengthy affairs that lack basis: Indictments

The preparation of indictments stands out as one of the most visible examples reflecting the abuse of judiciary. In principle, indictments prepared by public prosecutors should be prepared in a reasonable time and in a justified manner based on concrete evidence if there is sufficient suspicion that the suspect has committed the alleged crime. In return, courts are responsible for overseeing whether the indictments are admissible, otherwise it must return them.

In practice, however, the first problem with the preparation of indictments is that they can take beyond a reasonable time, as well as be completed without concrete evidence and justification.

The European Union’s 2019 Turkey Report states that in 2018 there were 57,000 individuals in pre-trial detention – which accounts for almost 20 percent of the general prison population – waiting for the indictments to be prepared. Considering the high risk of being detained until the lengthy preparation of the indictments, this situation creates a “chilling effect” on journalists and media workers.

The government reportedly plans to define a time limit for preparing an indictment and arranging detention periods accordingly as part of the most recent judicial reforms package being drafted. However, debates in Turkey over the binding nature of the ECtHR judgments and local courts’ refusal to implement these judgments raise the question of the sincerity of such reforms and how effectively these reforms would be implemented in practice. Furthermore, setting a time limit for indictments will not on its own be sufficient to solve this systematic problem. A time limit under the disguise of reform will only cause the indictments to be prepared hastily and contrary to expectations, without sufficient evidence and justification.

The second problem concerning the indictments is the lack of sufficient reasoning and justification. Any judicial action against press freedom (or free expression in general) must be set forth with sufficient clarity and fully justified. In this context, the prosecution is responsible for providing a reasonable justification and evidence and the courts must provide a reasonable explanation when rendering judgments. Otherwise, the person’s right to a fair trial will be violated.

Article 141 of Turkey’s Constitution requires courts to render reasoned written judgments. Although this provision appears to be for courts to comply with, all actors in criminal proceedings should be expected to comply with this provision, especially in accordance with the presumption of innocence. This includes indictments and final opinions submitted by prosecutors’ offices. Despite these requirements, the arbitrariness and abuse of legal prosecution has been at the heart of the continuous legal harassment against journalists in Turkey.

A Case Without a “Reason”

Perhaps the most recent example that demonstrates the lack of reasoning and justification in judicial processes regarding freedom of the press is the case against journalist Ender İmrek.

Following a complaint from Emine Erdoğan, President Erdogan’s wife, Ender İmrek faced prosecution under Article 125 of the TCC and a possible sentence of up to 2 years and 4 months in prison for his article published in Evrensel Newspaper on June 29, 2019 with the headline “Shiny, Shiny Hermes Bag”. İmrek was acquitted on December 2, 2020. However, recently both the complainant Erdoğan and the public prosecutor’s office appealed the acquittal.

As mentioned above, although the case ended in acquittal, apart from the chilling effect on the journalist, the case is peculiar for its outrageous lack of “justification”. By looking at the overall documentation, there is no reasonable justification put forward in the case file. Neither the court, the prosecutor nor the complained revealed which specific statements used by İmrek had constituted an insult. This attitude can be observed during nearly all stages of the trial.

In İmrek’s article, it is apparent that there is a valid criticism that tries to draw attention to the lawsuit filed against Canan Kaftancıoğlu, the İstanbul chair of opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), who was on trial on charges of insulting the president over a number of social media posts six years ago. In the article, İmrek suggests a contradiction between the Kaftancıoğlu case and the first lady’s carrying a bag worth 50,000 dollars. “While the people are suffering from hunger and poverty, carrying a bag worth 50,000 dollars is not an insult to the public, but what Canan Kaftancıoğlu says is an insult to the president”, İmrek says. Such criticism appears to be completely within the limits of freedom of expression and required to have higher protection as the subject falls within public interest.

The indictment alleged that in the process of comparing First Lady Erdoğan and CHP Istanbul Provincial Chair Canan Kaftancıoğlu, İmrek allusively implied the good qualities found in Kaftancıoğlu did not exist in Erdoğan and therefore humiliated her. However, there is no evidence provided as to which statement gives this impression.

At this point, it is useful to list other peculiarities that have been observed during the judicial process. In addition to the indictment, it is also observed that the prosecutor’s final opinion consisted only of a sentence, stating that the defendant should be sentenced. The prosecutor’s later appeal against İmrek’s acquittal also consisted only of one sentence with the claim that the decision had been unlawful.

As for the court itself, even though the indictment lacked evidence and justification, instead of returning it, the court accepted the indictment and began the trial. Later, although the court acquitted İmrek of all charges, it did not evaluate which statement would constitute an offence of defamation, nor did it address this deficiency during the trial. The court’s reasoning behind the verdict stated that the elements of the claimed offense have not been constituted and the article in question falls within the limits of the press freedom, yet still leaving İmrek in dark as to which specific phrase caused the prosecution.

Because of the indictment’s lack of argument or explanation, neither İmrek nor the court knew what İmrek did do by saying (or not saying) to insult First Lady Erdoğan. The only tangible and known reason is the allegation that First Lady Erdoğan was insulted by not being attributed with good qualities that Kaftancıoğlu possesses. On top of that, according to İmrek, when his lawyers asked for the reasoning of the trial, the prosecutor replied by saying “no need for explanation for those clever enough”.

In an interview with IPI, İmrek evaluated the case underlining the lack of justification. “There is an attempt to oppress without justification”, İmrek said. He also stated that even after he had read the article numerous times, he still cannot determine what statement could be considered as an insult. He further stated that his article was to draw attention to the contradictions on a subject on which was extensively discussed in public space. In this respect, the entire judicial process, according to İmrek, was “a file that should not have reached the stage of prosecution and should be completed during the investigation phase”.

Regarding the appeal process, İmrek pointed out the difficulties of even making a defence against a case when you don’t know the reasoning. İmrek told IPI that if there is still a commitment to freedom of expression and the rule of law in Turkey, he believes the acquittal decision will be upheld.

As can be observed from this case, there is a highly dangerous trend of using the judiciary to put the press under intense pressure. Cases such as İmrek’s which lack sufficient reasoning and justification demonstrate the arbitrary, yet systematic, nature of the ongoing legal harassment against journalists in Turkey. This systematic intimidation causes journalists to be affected, both mentally and financially, thereby leading to expand existing practice of self-censorship. If the judicial reforms on the current agenda appear to be genuine and sincere, this system of repression must first end.