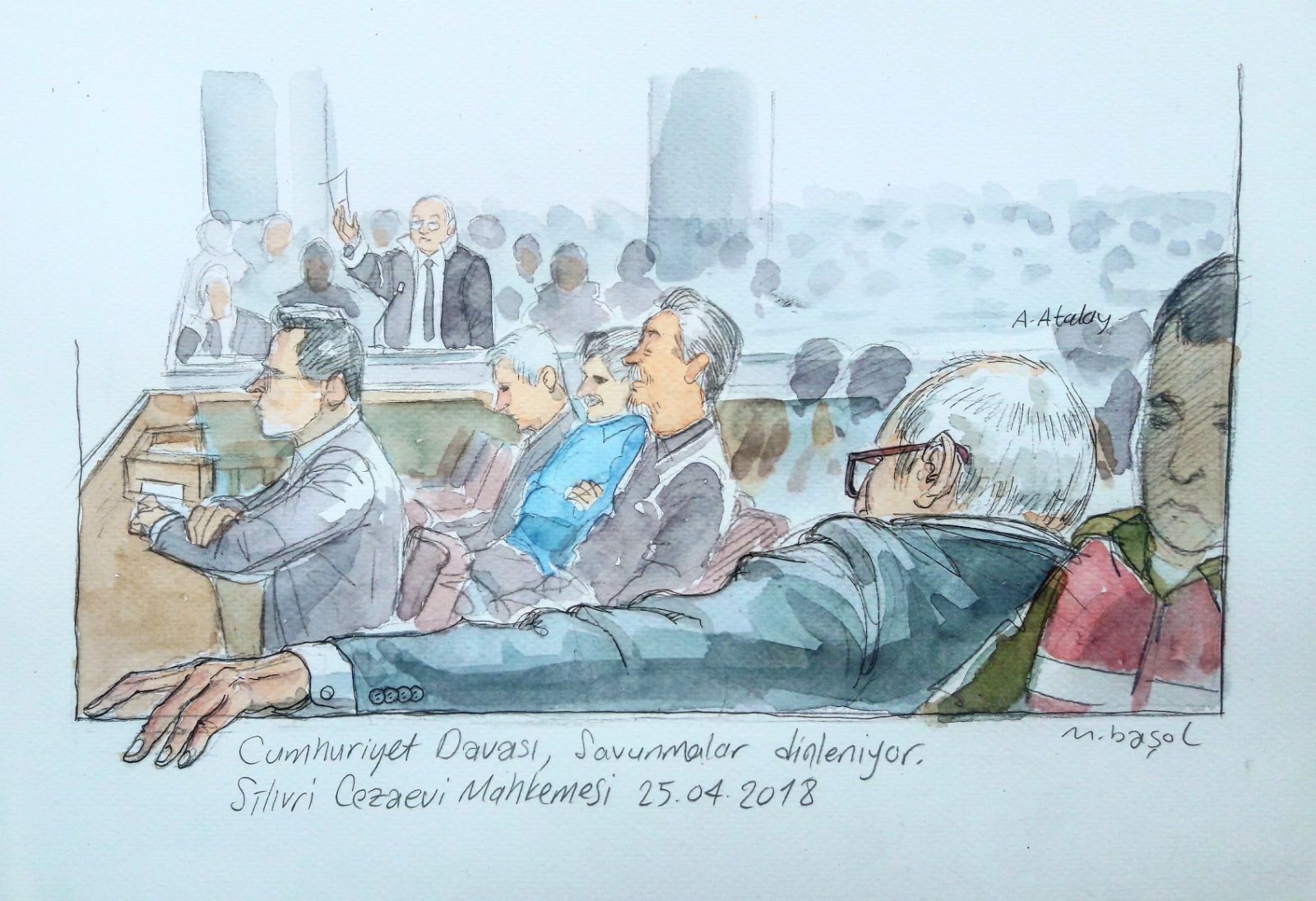

After 17 months of judicial proceedings and a collective total of almost 10 years of pretrial detention, the trial of journalists and staff with Turkey’s secular daily Cumhuriyet newspaper ended on April 25, 2018, with three acquittals, the separation of two cases, and 14 inordinately harsh custodial sentences ranging from two-and-a-half to 10 years.

The case against key figures at one of Turkey’s last three independent daily newspapers involved no crime, no evidence and no justice. IPI was present in court to monitor six of the seven hearings in the trial, with each proving as disrespectful to the notion of justice as the others. The trial was permitted to progress in a landscape devoid of any guarantee of the right to an impartial, speedy and fair trial as enshrined in the Turkish constitution, European case law and the European Convention on Human Rights.

It will never be acceptable to deprive innocent people of their freedom or to cast aspersions over their reputation and that of their newspaper simply because they did their jobs as critical, independent journalists.

The seventh and final hearing in the case took place on April 24 and 25. The trial was due to run until Friday, April 27, but the defence team advised most defendants to add nothing further to defence statements already given in July 2017. Exceptions were made in the cases of Cumhuriyet CEO Akin Atalay and columnist Kadri Gürsel, who is also a member of IPI’s Executive Board and the chair of IPI’s Turkey National Committee.

Proceedings began at 10:20 am on Tuesday, April 24 in a basement courtroom at Silivri high security prison outside Istanbul with the judge’s making a statement to defend himself over his closing remarks in the previous hearing. The judge expressed anger over the “disrespectful” manner in which a “journalist” had criticized the remarks. He claimed that each case had a different “atmosphere” that allowed for a unique manner of addressing the defendants, permitting him to have told Cumhuriyet Editor-in-Chief Murat Sabuncu to “go and see the Bosphorous”.

Next, Cumhuriyet CEO Akın Atalay, who was one of only two defendants still held in pretrial detention, took the stand to answer to a new file of evidence against him.

Weak new ‘evidence’

The new “evidence” against Atalay consisted of five files taken from random locations on Atalay’s laptop. The images and documents ranged from a photograph of 100 generals, to a photograph of a hand-written series of tweets on headed paper by former Cumhuriyet Editor-in-Chief Can Dündar and a poem on a page bearing the image of Fetullah Gülen, the exiled cleric whom Turkey blames for the 2016 coup attempt. The prosecution, which did not provide the directory addresses or file locations of these documents, claimed these files constituted proof of Atalay’s links to Gülen’s movement.

Through a series of screen shots, Atalay specified the original file locations and showed that the files were related to news articles published by Cumhuriyet in relation to the attempted coup or to legal cases against the newspaper. In other words, they were entirely innocuous and correctly archived materials.

This absurd, hastily assembled “proof” of Atalay’s links to terror groups was a perfect example of the disregard for judicial rigour that was a hallmark of the show trial against Cumhuriyet.

Following Atalay’s presentation, Gürsel took the stand to address, one by one, the accusations against him. The “evidence” in Gürrsel’s case consisted of no more than a news article in which he likened President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to a bad father and SMS messages to which he had not replied and that were sent by a members of the public, some of whom had downloaded an encryption programme called ByLock believed to be used as a secure communication method by members of the Gülen movement.

Unanswered SMS messages ‘not proof of terrorist activity’

In his defence statement, Gürsel told the court:

“In 32 years as a journalist, I’ve never been asked to explain one of my articles. Journalism is the art of choosing the right words. As for my having been in touch with (allegedly Gülen-linked) Cihan News Agency, there was one phone call. In 44 months I had only six calls with (allegedly Gülen-linked) Feza News Agency. It is unbelievable that I could be accused of aiding and abetting a terror organization based on these calls. Feza News Agency called me a couple of times to get my opinion on various subjects. The compiler of the indictment must have ignored the fact that I am a journalist. You cannot accuse me of sharing the same political views as people who call me up. Journalists have the right to speak to a whole range of people in the country in order to write full and well-founded journalistic articles.”

Atalay then took the stand once again to present his final defence, declaring that the primary role of a newspaper should not to be to make money but to present news, truth and criticism to the public.

“A newspaper is there to serve the people, not the government”, he said. “You cannot destroy this newspaper by trying it on false evidence, by threatening it or by throwing its journalists in jail. These journalists will do their jobs and will not be silenced or frightened.”

The majority of the remaining defendants, when they took the stand, said that they had nothing to add to their defence statements given in July 2017.

During the afternoon session on July 24, four defence lawyers spoke on behalf of their clients. The first to speak was the lawyer for Kemal Aydoğdu, who faced charges relating to his social media account @jeansbiri and alleged links to the Gülen movement. Aydoğdu never at any time worked for Cumhuriyet and it remains an unanswered question as to why his case was added to that of Cumhuriyet staff and journalists after the initial case began.

The Cumhuriyet legal defence team took turns speaking, with some lawyers presenting joint arguments that had been worked on by several colleagues. All were put in the absurd position of having to repeat sound and simplistic legal arguments to counter the absence of evidence, a fundamentally flawed indictment and an unfair trial.

The first prosecutor assigned to the Cumhuriyet case stepped down after a court case was filed against him in Ankara in late 2016 for alleged membership of the Gülen organisation and for signing documents that authorised the illegal tapping of telephone conversations. The defence revealed in this final hearing that the current prosecutor had also led a case in 2011 against Cumhuriyet for insulting Gülen, the exiled cleric whose organisation Cumhuriyet were on trial accused of having supported.

Court operating outside the law

On day two of the hearing, two of the most prominent defence lawyers for Cumhuriyet, Tora Pekin and Fikret İlkiz, offered closing statements. Their arguments centred on the principles of freedom of expression, the right to an impartial and fair trial, and basic requirements related to indictments and evidence.

“The indictment, in order to be a legal document must be comprised of legal arguments that are backed up by evidence”, Pekin told the court. “A fair trial can only be secured if the judges are operating within the law.”

Those arguments, citing case law from the UK, Italy, Poland and Denmark as well as the Turkish constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights, were made in vain. But despite the baseless indictment and a lack of evidence and relevant witnesses, Pekin and İlkiz did their job as professionals, eloquently reiteraring the basics of judicial protocol so openly flouted by an administration that considers itself above the law.

“Regarding this case: History will write one truth”, İlkiz remarked. “You found nothing here but journalism and legal defence.”

In the end, the judges were unmoved, resulting in a travesty of justice. IPI has called for these verdicts to be overturned at the earliest opportunity and for the appeals court to fully compensate the defendants for the years they spent in pretrial detention.

The Cumhuriyet hearings were a cruel farce. Going forward, it is up to Turkey’s higher courts to reclaim the independence of the justice system. The European Court of Human Rights and the Council of Europe must support them in this effort.

In the week following the verdict the prosecutor did not object to the length of the sentences given. The appeal is expected to be heard at the Supreme court within 4 months.

Sentencing:

Cumhuriyet Executive Board Chair Akın Atalay – 8 years 1 months and 15 days

Orhan Erinç – 6 years and 3 months

Murat Sabuncu – 7 years and 6 months

Kadri Gürsel – 2 years and 6 months

Güray Öz – 3 years and 9 months

Musa Kart – 3 years and 9 months

Aydın Engin – 7 years and 6 months

Hikmet Çetinkaya – 6 years and 3 months

Ahmet Şık – 7 years and 6 months

Mustafa Kemal Güngör, Önder Çelik and Hakan Kara – 3 years and 9 months

Ahmet Kemal Aydoğdu – 10 years

Emre İper – 3 years 1 month and 15 days

Bülent Utku – 4 years and 6 months

Turhan Günay, Bülent Yener and Günseli Özaltay were acquitted

The files of Can Dündar and İlhan Tanır were separated from the others in the case